My house is French, my land is Russian

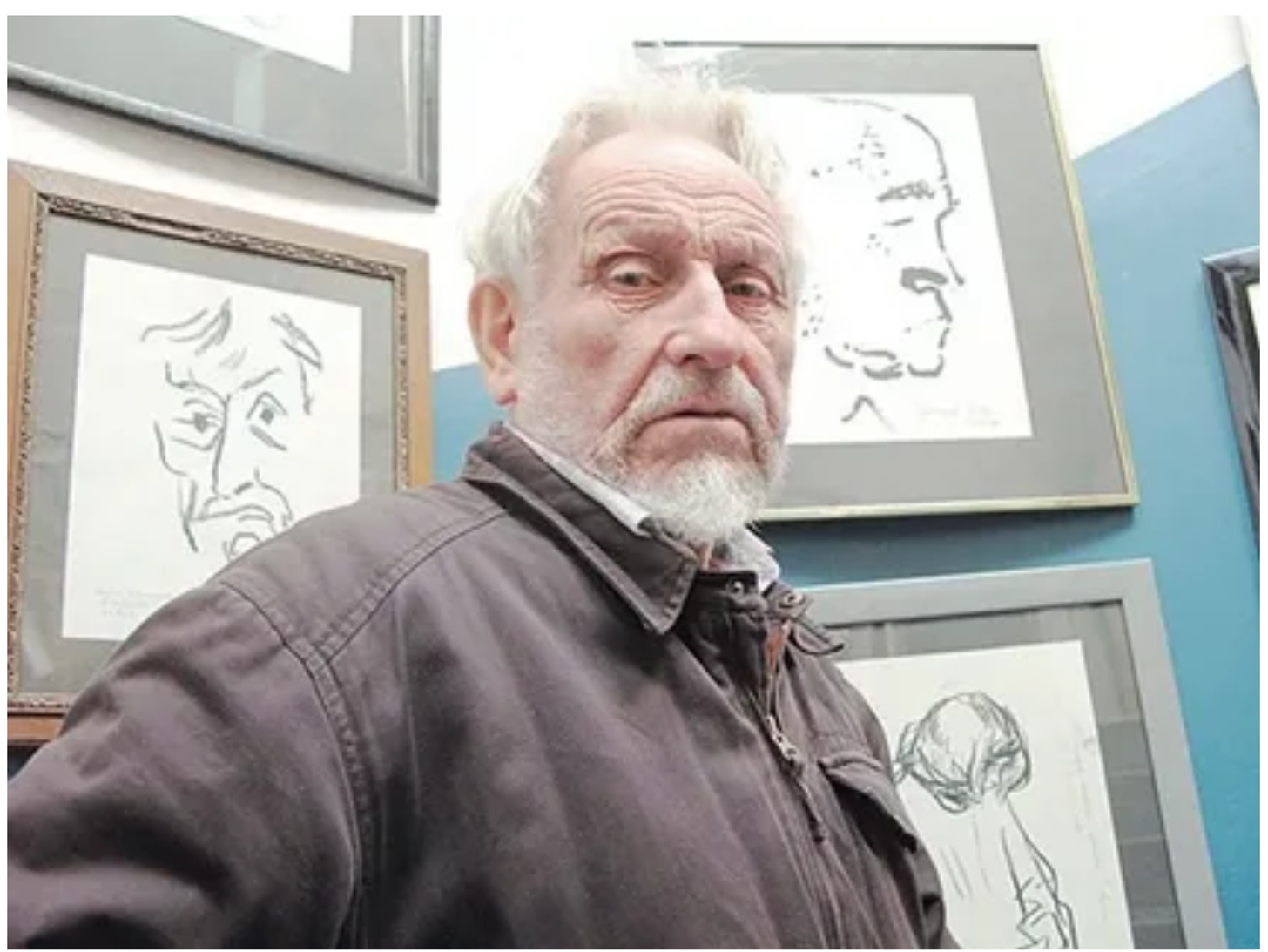

How Nikolai Dronnikov became a chronicler of our diaspora in Paris and immortalized Notre-Dame

Kolya, you are a titan, the mountains rumble

Kolya, you are a man, the meadows sing

Kolya, you are a master, the rivers whisper

Kolya, you are a friend, Aigi creaks

— Gennady Aigi to Nikolai Dronnikov

In the picturesque town of Honfleur on the Atlantic coast, an exhibition titled “Nikolai Dronnikov: The Russian Soul of Paris” welcomes visitors. It is dedicated to the 94-year-old artist, a senior who settled in France in the early 1970s.

The current retrospective of Nikolai Dronnikov showcases Paris, its former beauty, as well as Russian landscapes, churches, and self-portraits. But no matter what he paints, we feel the soul of a great painter, said the gallery owner of "La Brocanterie" to "Literaturnaya Gazeta". - For us, he is the most Russian of French painters and the most French of Russian painters. Since 2008, we have exhibited Dronnikov in Honfleur, year after year, with unwavering success, recalls the gallery owner. Exhibitions have also been organized in Nice, Marseille, Strasbourg, at the Château de Villandry on the Loire, and, of course, in Paris, where Nikolai has exhibited his works not only in galleries but also at the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

None of the Russian masters have dedicated as many paintings to the Capital: he painted Notre-Dame Cathedral in every season and at all times of the day, its bridges, and the life of Parisian beggars. Some touching works depict the Pokrovsky Convent, founded after World War II in Bussy-en-Othe in Burgundy. Many paintings depict typically Russian places – cathedrals, monasteries, fairs, snow-covered villages... At the same time, French motifs often echo Russian reminiscences.

Nikolaï Egorovich Dronnikov became known as the “chronicler of the Russian diaspora” – with his portraits of famous compatriots of different generations, such as: Princess and writer Zinaida Shakhovskaya, Irina Odoevtseva, Serge Lifar, Alexandre Solzhenitsyn, Andrei Tarkovsky, Mstislav Rostropovich, as well as Bulat Okudzhava, Bella Akhmadulina, Iosif Brodsky, Vladimir Vysotsky, Andrei Voznesensky.

Some series of portraits were printed by him and at home with his illustrations on a personal printing press. Using the method of “samizdat,” a clandestine self-publishing and printing of 40 to 50 copies.

"... With Nikolai Egorovich, we met many years ago at the prestigious Svyatoslav Richter festival, which was held annually in the 13th-century barn of Meslay, adapted for musical evenings of the great pianist in central France.

Nikolai Dronnikov drew Mstislav Rostropovich during his concerts, as well as other artists. He didn't like people posing for him. He preferred dynamic sketches: a musician playing, a poet reciting his poetry, a bard singing, a conductor conducting... During one of our conversations, Nikolai said that he had painted about a thousand portraits in total: “he has created a real encyclopedia of Russians abroad. It includes not only famous names but also my friends and acquaintances.”

The editor-in-chief of 'Izvestia' married him.

Nikolai Dronnikov was born in the now-deserted village of Budki in the Tula region, which, according to the latest census, is now inhabited by only one person. After serving in the army, he received academic education – he graduated from the School of Fine Arts founded in memory of 1905 in Moscow, then from the Surikov Institute. Nikolai Egorovich declares himself a “Cézannist” (a follower of Cézanne), while stating that he was and remains a Russian artist.

It is unknown to what extent the fascination with Cézanne and Matisse influenced Nikolai’s destiny, but he married French journalist Agnès, now deceased, who worked as a correspondent for Agence France Presse in Moscow.

Marrying a foreigner in the Soviet Union, bypassing all obstacles, was very difficult at that time. The very powerful editor-in-chief of the newspaper Izvestia, Alexei Adzhubey, helped them, as well as the chance of Khrushchev’s “thaw”. Nikolai and his wife left for France with almost nothing: Nikolai burned his paintings, his diaries, and his archives in a ravine, as if he wanted to make a clean break with the past.

The newlyweds settled in Agnès’s family nest in Ivry-sur-Seine, a suburb of Paris. For more than a century, this suburb has been one of the strongholds of the Communist Party, and its city still bears the names of Lenin (former Stalin Street), Gagarin, and the head of the PCF, Maurice Thorez. The city is crossed by Boulevard de Stalingrad. Recently, Marina Vlady settled in Ivry-sur-Seine. In the Ivry cemetery rest the famous painters Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov, whose graves Nikolai Dronnikov maintained.

On the gate of his house, Nikolai hung a formidable two-headed eagle, which he himself made of tin. The main Russian symbol to which he remains faithful today. “My house is French,” the artist likes to say to his guests, “but the land is Russian; it was brought from Russia and scattered in my yard.”

In the house and in the yard, “lives” the Raven, captured by Nikolai in his paintings, drawings, sculptures. “A bird of prey, evil and foreboding, it is better to have it as a friend,” Nikolai Yegorovich explains to me. “It is my amulet, my talisman.”

A Hermit apart from the mainstream

Nikolai Dronnikov arrived in Paris a few years before other Russian artists — nonconformists who had to leave the Soviet Union at the end of the 1970s. Proud and stubborn, Dronnikov always kept to himself, avoiding the mainstream of the “second Russian avant-garde” in France. His relationship with them had failed; their “aesthetic differences” were too great.

He considers himself a skhimnik — a hermit who rarely leaves his “cell” to face the outside world. But despite his apparent austerity, he is a receptive man, open-minded, and ready to help — especially his fellow artists who live in Paris.

It was there that he met the remarkable Chuvash poet Gennady Aigi, and he designed the staging of Aigi’s poetry evening at the Pompidou Center. He manually printed Aigi’s poetry collections at home, visited him in Cheboksary, where he also held an exhibition of his works. Upon the death of his friend, he responded with the book Requiem for Gennady Aigi.

He also maintained a close connection with Konstantin Danzas, a distant descendant of the witness to Pushkin’s duel, whose ancestors had fled to Russia during the French Revolution in February 1789, and later returned to France after the October Revolution of 1917.

Finally, in the 21st century, Nikolai Dronnikov returned several times to Russia with his paintings and books. One of his first exhibitions in Ulyanovsk (formerly Simbirsk), the hometown of Ivan Goncharov, featured Dronnikov’s illustrations of the novel The Ravine.

Previously, Dronnikov had helped the museum recover documents about Sasha Simon, the last descendant of Goncharov, with whom he had a close friendship. Simon, a journalist, spoke Russian fluently and worked for many years in Moscow as a correspondent for Le Figaro. He authored a dozen books on the Soviet Union and was eventually expelled from the country.

The Saint Petersburg Museum invited Dronnikov to take part in the Russian Paris exhibition, organized for the 300th anniversary of the founding of Saint Petersburg. He exhibited at the Pushkin National Museum — first with his portraits, then with books printed by the artist himself at home in Ivry-sur-Seine.

Nikolai Yegorovich Dronnikov generously donated his paintings in Russia — the Cheboksary Art Museum received about sixty of his works. He donated portraits of the famous singer to the Vladimir Vysotsky Museum in Moscow.

“Art must be accessible to everyone, whether in Russia or in France,” says Nikolai Egorovich Dronnikov, formulating his artistic credo. “Let painting be present in every home. That’s why I sell my paintings at low prices or give them as gifts. I don’t believe beauty will save the world, but it can heal the heart and the mind, it can uplift a person broken by fate,” says the professor, the hero of a story by Gleb Uspensky, who once saw the Venus de Milo at the Louvre. Before encountering the statue of the goddess, he saw himself as a broken man — but afterward, he felt as if wings had grown on his back.

— Yuri Kovalenko, correspondent of "Literaturnaya Gazeta," Paris